Test Driven Development with MVVM

I’ve been a consultant in many projects for client side developments, and compared to the backend the test coverage is usually very low. In fact in many projects unit test coverage is zero percent. And I do understand that. Many UI technologies make it really hard to write simple unit tests. It’s very possible to deploy a product that behaves reasonably well without ever writing a unit test. Everyone who tells you something else is simply a liar. But maybe his intentions are good. Most likely he’s a consultant like me who wants to convince you that you need to write unit tests, because it will make your life so much easier.

Test Driven Development means "Test first"

If you’re able to test the behaviour of your UI in simple unit tests, you will gain a lot of confidence in the quality of your product. But not only this, you can also start using Test Driven Development practices, that will simplify your work process by giving you a clean, success oriented and structured way to easily acomplish things.

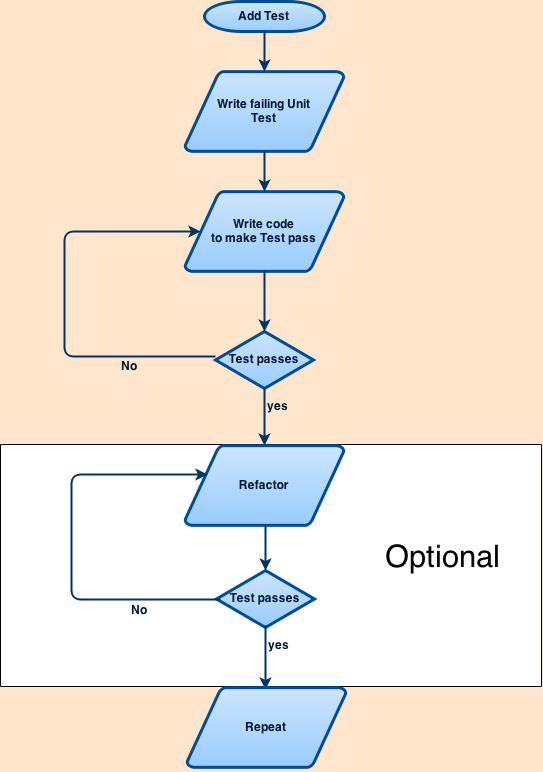

Whenever you’re creating a form, a dialog, or any other UI - don’t bother writing UI code. Instead start by writing a test for one of the aspects in your spec. Then quickly implement the tested functionality until the test - and all other tests in your project - succeed. As a last step clean up and refactor what you created. Then repeat this process with the next test. As soon as all the tests succeed you’re done. That’s TDD in a nutshell!

Is your UI Toolkit Test friendly?

The whole process works great and is a real productivity booster - if your UI technology supports it. That last “if” turns out to be a big problem with todays UI technologies. They are often mixing view and view logic in a way that cannot easily be untangled. You need to set up a lot of things for your tests to work. Let’s take JavaFX as an example. Even though there’s a separation between design and view logic ( via FXML and the accompanying controller ), this separation isn’t absolute. As a result you end up with a controller that knows and manipulates your Labels and Buttons.

This means you have to initialize those for the test. Manipulating UI Elements must happen in the UI Thread. But your unit test doesn’t run on this thread.

As a result you need to create or use a framework to solve this, and you end up with a lot of added complexity. A lot of developers - or their project managers -

don’t want to go this extra mile. That is the death of unit tests in their project.

You might suggest that it still pays to do this extra effort. I agree. But the reality shows that it’s not happening.

DukeScript to the rescue

If your UI Technology isn’t test friendly, it’s probably time to look for a better technology.

You’re reading an article about DukeScript, so it’s obvious what technology I’ll suggest now. In DukeScript we’re using a Model View ViewModel (MVVM) architecture. This has a lot of benefits for developers. Obviously it allows a clean separation of design in the “View” part and UI logic in the “ViewModel” part. It is also perfect for Test Driven Development.

You simply start by writing a unit test for the ViewModel. Then you create the ViewModel class (if it doesn’t exist yet) and implement the functionality to pass the test. Since the ViewModel knows nothing about the View, there’s no need to bother implementing the View yet. You can perfectly test your UI without it. You can test the pure functionality. As a result your test code and the ViewModel itself will be very concise.

A little example

We want to create a very simple Todo-List. The UI should have a TextField on top to enter new Items and a Button next to it to add them. The Button should only be enabled if the item entered is at least three letters long. Below these inputs we want to show the actual todo list. The user can select an item and delete it. This is done via a button below the list. It should only be enabled when an item is selected. When the button is pressed, the selected item should be removed from the list.

Let’s develop this UI using TDD. We start with iteration 1. Let’s test enabling and disabling the “add”-button first:

import static org.testng.Assert.*;

import org.testng.annotations.Test;

public class DataModelTest {

@Test

public void addButtonEnabled() {

TodoListViewModel model = new TodoListViewModel();

model.setInputText("Bu");

assertFalse(model.getAddEnabled());

model.setInputText("Buy");

assertTrue(model.getAddEnabled());

model.setInputText("Bu");

assertFalse(model.getAddEnabled());

}

}Now we need to write the ViewModel that passes this test:

@Model(className = "TodoListViewModel", targetId="", properties = {

@Property(name = "inputText", type = String.class)

})

final class TodoListViewModelDefinition {

@ComputedProperty static boolean addEnabled(String inputText){

return (inputText != null && inputText.length() > 2);

}

}Execute the test, it should pass. If you know what you can do with declarative bindings, you might suggest that we don’t need that ComputedProperty, because you can solve that declaratively in the view. That’s true, but then you can’t test it in a simple unit test.

That was fairly simple. We can skip the refactoring step, because the code looks OK. Ready for iteration two. Let’s write another test. This time we test if the “add”-button does it’s job:

@Test

public void addButtonAdd() {

TodoListViewModel model = new TodoListViewModel();

assertEquals(model.getTodos().size(), 0);

model.setInputText("bu");

model.addTodo();

assertEquals(model.getTodos().size(), 0);

model.setInputText("buy milk");

model.addTodo();

assertEquals(model.getTodos().size(), 1);

assertEquals("", model.getInputText());

}Now lets alter the ViewModel to also pass this test:

@Model(className = "TodoListViewModel", targetId = "", properties = {

@Property(name = "inputText", type = String.class),

@Property(name = "todos", type = String.class, array = true)

})

final class TodoListViewModelDefinition {

@ComputedProperty

static boolean addEnabled(String inputText) {

return (inputText != null && inputText.length() > 2);

}

@Function

@ModelOperation

public static void addTodo(TodoListViewModel model) {

if (model.getInputText() != null && model.getInputText().length() > 2) {

model.getTodos().add(model.getInputText());

model.setInputText("");

}

}

}Perfect all our tests pass. The “add”-function works. But the code is not nice. There’s a duplication for validating the input. We could check for isAddEnabled, but that would be ugly. First we might decide to add new entries via a different channel, and second the method name should reflect the purpose of the method. So let’s refactor it:

@Model(className = "TodoListViewModel", targetId = "", properties = {

@Property(name = "inputText", type = String.class),

@Property(name = "todos", type = String.class, array = true),

@Property(name = "selectedItem", type = String.class)

})

final class TodoListViewModelDefinition {

@ComputedProperty

static boolean addEnabled(String inputText) {

return isValidInput(inputText);

}

@Function

@ModelOperation

public static void addTodo(TodoListViewModel model) {

if (isValidInput(model.getInputText())) {

model.getTodos().add(model.getInputText());

model.setInputText("");

}

}

private static boolean isValidInput(String inputText) {

return (inputText != null && inputText.length() > 2);

}

}Now it’s time for the “delete”-button. We’ll first test if it’s correctly enabled and disabled:

@Test

public void deleteButtonEnabled() {

TodoListViewModel model = new TodoListViewModel();

assertFalse(model.isDeleteEnabled());

model.add("buy milk");

model.getSelected().add("buy milk");

assertTrue(model.isDeleteEnabled());

}Again lets alter the ViewModel to pass this test;

@Model(className = "TodoListViewModel", targetId = "", properties = {

@Property(name = "inputText", type = String.class),

@Property(name = "todos", type = String.class, array = true),

@Property(name = "selected", type = String.class, array = true)

})

final class TodoListViewModelDefinition {

@ComputedProperty

static boolean addEnabled(String inputText) {

return isValidInput(inputText);

}

@Function

@ModelOperation

public static void addTodo(TodoListViewModel model) {

if (isValidInput(model.getInputText())) {

model.getTodos().add(model.getInputText());

model.setInputText("");

}

}

private static boolean isValidInput(String inputText) {

return (inputText != null && inputText.length() > 2);

}

@ComputedProperty

static boolean deleteEnabled(List<String> selected) {

return (selected != null && selected.size() > 0);

}

}The code looks OK, no refactoring required. And finally we’ll test if pressing the delete-button really removes the item from the list:

@Test

public void deleteButtonDelete() {

TodoListViewModel model = new TodoListViewModel();

model.getTodos().add("buy Milk");

assertEquals(model.getTodos().size(), 1);

model.getSelected().add("buy Milk");

model.deleteTodo();

assertEquals(model.getTodos().size(), 0);

assertEquals(model.getSelected().size(), 0);

}Here are the required changes to the ViewModel:

@Function

@ModelOperation

public static void deleteTodo(TodoListViewModel model) {

List<String> selected = model.getSelected();

for (String selected1 : selected) {

model.getTodos().remove(selected1);

}

model.getSelected().clear();

}Done, all the tests pass, our ViewModel works. Now we can start developing the View part:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Todo List</title>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8">

</head>

<body>

<input data-bind="textInput: inputText" />

<button data-bind="enable: addEnabled, click: addTodo">add</button><br>

<select style="width: 100%" size=10 data-bind="foreach: todos, selectedOptions: selected">

<option data-bind="value: $data, text:$data"></option>

</select>

<button data-bind="enable: deleteEnabled, click: deleteTodo">delete</button>

</body>

</html>All the bindings are declarative and simple. They don’t have complex binding logic. That is an important part. If we start writing complex bindings, we will often unintentionally put UI logic into the View where it is hidden from our test, and we’ll loose the benefits of TDD. But with simple bindings like in this case there’s not much that can go wrong, and we can wait with confidence for the integration tests (which are also very simple to do with DukeScript).

Obviously there is some cheating involved in this process ;-). I sometimes add the required Properties just before I write the test. That prevents unnecessary little bugs and typos like writing “getEnabled()” instead of “isEnabled()”. But generally I like to write the test as a way to design the API. It forces me to take the API user perspective. That helps to design an API that is clean and simple.

If you’re to busy to create a project and copy and paste the above code (who isn’t?), you can also checkout this project on Github

And here’s the bck2brwsr version of the example - I admit it could use some styling.

DukeScript - be productive!